The Tuesday Composition: Lighting and Composition

If you like this article, you can now get the book! Joe has expanded the “Tuesday Composition” series into an inspiring new ebook on composition, especially for nature photography. Check it out: The Tuesday Composition.

A few years back, Frans Lanting said something in passing that’s really stuck with me, I presume it’s an old studio lighting maxim:

Front-lighting for color, side-lighting for texture, back-lighting for form.

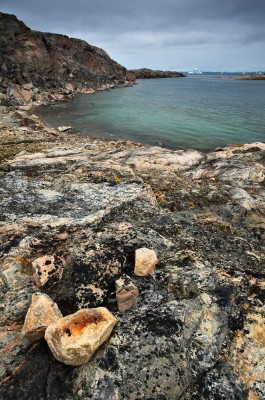

This line is pretty much a recipe for how to light an object in the studio depending on what aspect of it you want to emphasize. Got a colorful subject? Start by photographing from the same direction as the light is coming from. Want texture? Make sure the light is coming in from the side, that way it’ll be raking across the front of the subject you’re looking at and showing shadows on even the smallest bits of texture. And want to show the shape of something? Backlight it, and create a silhouette.

Obviously it’s simplistic (as any nine words of advice must be), but it’s not a bad place to start when thinking about lighting.

In addition to light direction, we also talk about the difference between soft (wide) light sources and hard (tiny) light sources. Hard lighting tends to pick up more texture by creating better-defined shadows than soft lighting.

What does all of this have to do with composition?

While we have a great deal of flexibility in lighting subjects in the studio, many of us who photograph nature, or events, or sports often have a little less room to organize our environment the way we’d like. We might have a couple different objects in our scene, and perhaps we’d like the form of one of them juxtaposed with the color of another and the texture of a third, and the light might be doing something else entirely. (more…)